Norse Mythology

If there is one thing that I have learnt in my research of Vikings and Norse history, it’s that the line between myth and reality is blurred to such an extent that we might never know which is which in some cases.

Norse mythology has come to us through writings which have been dated to around the thirteenth century, notably the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda. Both are retellings of original Norse myths in the form of sagas.

The most notable collection of Poetic Edda poetry is contained in a document called the Codex Regius, which is an Icelandic manuscript written in 1270. The author of the manuscript is unknown, as is the original teller of the poems, although presumably they are the result of the gathering of many stories handed down verbally.

The Prose Edda was written by Snorri Sturluson in the early thirteenth century, and is a retelling of the Poetic Edda in the form of prose in an attempt to present the stories in a more consistent and coherent way.

Another source of Norse stories is the Saga of the Volsungs, which was written in the late thirteenth century, and covers legends about the Volsung clan (including important characters such as Sigurd and Brunhild).

As you can see, the source material was written after the end of the Viking era and it is generally believed that some of the stories might have been changed to accommodate Christian sensitivity (for example around the role of women).

So, there are many scholars who spend their time interrogating the source material, hypothesising their true meanings.

For me, I have felt perfectly comfortable foraging in the retellings, and managing to resist the temptation to dive down rabbit holes of research into translations of the source material.

The book I have relied upon for this post is “Norse Mythology – the gods, goddesses, and heroes handbook” written by Kelsey A. Fuller-Shafer, PhD and illustrated by Sara Richard. I confess that I was first attracted to it because it was short (just as well given my time pressure at the moment) and because it has the most marvellous illustrations. Now that I have read it, I’m delighted with my choice. The chapters are well organised, easy to read, and engaging. Moreover, I feel that I’ve been delicately guided through the complicated nuances of Norse history and mythology without being confused by the introduction of too many conundrums (but just enough to make it fascinating).

So, without further ado, I will provide my summary of the characters, and groups of characters, which caught my attention.

Aesir, Vanir and Jotun

The Aesir and the Vanir are the two families of gods in Norse mythology. The Aesir are more powerful and they lived in Asgard. The Vanir lived in Vanaheim.

Jotuns are mythological beings who had similar powers to the gods, but were generally portrayed as the troublemakers or enemies of the gods. While Jotun is normally translated as ‘giant’, they are actually similar in size to the gods.

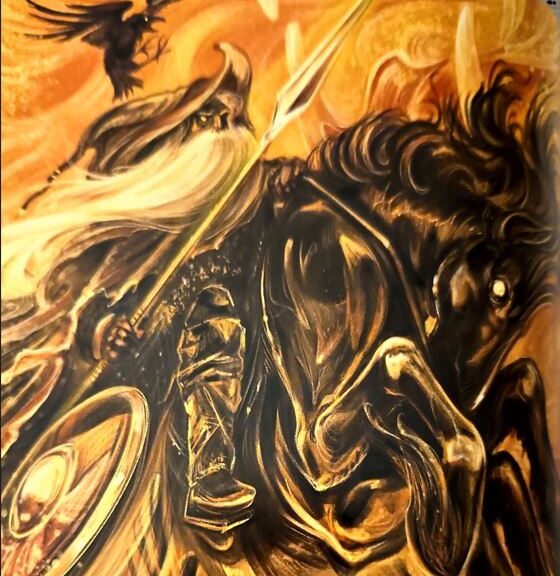

Odin is the leader of the Aesir, and is associated with war and knowledge (among other things). He is preoccupied with obtaining as much knowledge as possible to avert the end of the world (Ragnorok)

Thor is one of Odin’s sons and is known for his strength and fearlessness, as well as his insatiable appetite (yes, food and drink). Thor’s hammer (called Mjolnir) is legendary. He also had a magic belt.

Frigg was Odin’s wife (although not Thor’s mother, who was a Jotun). Frigg is associated with marriage and motherhood.

Balder was the favourite son of Odin and Frigg. The story of his untimely death is worth reading.

Freya is often referred to as the goddess of love and fertility. She was a Vanir who was integrated into Aesir society (intermingling happened). She owned a cloak of falcon feathers which gave her the power to fly. Freya lived in a hall called “Folkvang” to where half of the warriors slain in battle went in their afterlife.

The Valkyries were a group of female warriors who interfered in battle outcomes by carrying out Odin’s wishes as to which warriors survived and which died. The Valkyries then transported the souls of half of the best and bravest warriors to the afterlife of Valhalla, where they awaited the coming of Ragnorok when they would fight for Odin. (As mentioned above, Freya took the other half of the warriors to Folkvang)

Loki was a Jotun, who existed in the worlds of both the Aesir and Vanir. He is a colourful character, sometimes solving problems with cunning and resourcefulness, and at other times just simply causing chaos.

Hel was Loki’s daughter. She was a personification of death, and was banished to be guardian of the underworld (also called Hel) by Odin.

In the book, Fuller-Shafer also writes about many notable human heroes, of which I will mention only two:

Hervor is one of the few female Viking warriors in Norse mythology, and her story reflects the challenges of following her warrior goals while being a woman.

Frodi was a legendary Danish King who is known for accomplishing a peaceful reign. I mention Frodi here because Tolkien borrowed the name Frodi for his character of Frodo, another peace-loving hero. In fact Tolkien was fascinated with Norse mythology and derived a number of characters, places, stories and languages for his books.

A quick word about a couple of other important concepts in Norse mythology:

Midgard is the land of humans (just one of nine realms in Norse mythology)

Yggdrasil is the life tree which connects all of the nine realms.

There is a very detailed creation myth, which I am not going to try and explain here.

Ragnorok is the destruction myth, describing how the world will end. As mentioned above, Odin is preoccupied with trying to change his fate. It is worth mentioning that after Ragnorok the universe will be reborn.