Arctic Art

I first got the idea for a post about Arctic art from “Arctic Dreams” – yes, the book which has inspired me with many and varied ponderings.

Lopez was describing a conversation with a retired scientist who was also an artist, when they were on Cornwallis Island in the Canadian Arctic. They marvelled about the fact that summer brings 24 hours of daylight which also delivers a “fullness and subtle quality of light”, together with a range of colour balances all within one day.

Lopez goes on to wonder why, then, European and American artists in the nineteenth century chose to often present landscapes in the context of arctic exploration, rather than celebrating the landscape itself. There was a recurrent theme of man v. the treachery of the land.

So, I decided that this would be an interesting idea to explore, and so dived into nineteenth century art which featured Arctic themes.

Having wandered around in that space for a while, I felt that I was just skirting around the edges of where I really wanted to be. And that was to learn something about the art which was actually being produced in the Arctic region.

That was when I launched into research into Greenlandic art, and have included some of these artists below.

European and American art of the Arctic

The Arctic was a popular subject. As explorers mounted expeditions, and often failed, there was sparked in the imaginations of Europe a fascination which was fed with stories and images (factual and imaginary)

The concept of imminent danger, from the elements and from wild animals, made the Arctic an oft-used subject. The loss of Sir John Franklin’s expedition promulgated further depictions, mostly imagined. There followed a fascination with what exactly happened to Franklin, a mystery which was to remain unsolved for a long time.

Furthermore, for some artists the Arctic was also representative of God’s supreme influence. These paintings displayed the idea of a ‘sublime’ and ‘glorious’ environment.

In art, therefore, as in exploration and discovery (in the wider sense), Europeans and Americans appeared to persist with this belief of their own supremacy…

… that other lands, animals and peoples were there to be tamed or exploited. Or otherwise defined within the context of their own concept of civilisation.

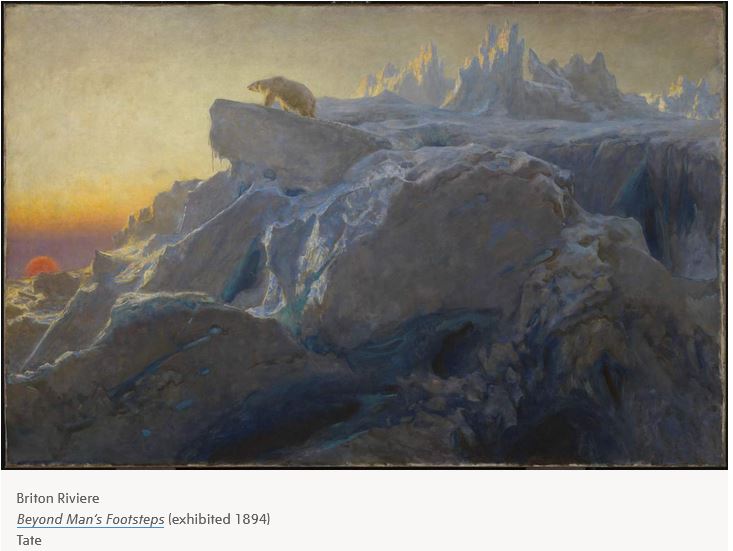

In Briton Riviere’s “Beyond Man’s Footsteps” (1894) the remote Arctic landscape, the solitary polar bear, and even the title, all direct our sensibilities to the notion of an inaccessible and dangerous land. Even the fact that the polar bear seems to be contemplating the view connects the viewer by suggesting wonder and appreciation. (Note that the polar bear was probably drawn from bears in the Zoological Gardens in Regent’s Park. )

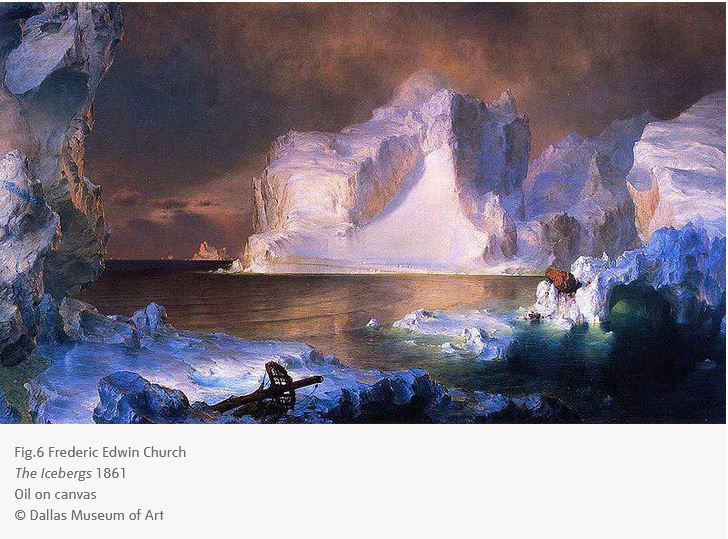

In Frederic Edwin Church’s “The Icebergs” (1861) we can see a distinct difference in the treatment of subject and light. The emergence of luminism, which was a style of American landscape painting which emphasised the effect of light on landscapes, did appear to have its influence on Arctic landscapes.

Interestingly, the original artwork did not contain the ship’s mast in the foreground. However, when it was first shown, the painting’s reception was cool because there was nothing in the painting depicting mankind, either directly or indirectly, and so the artist painted it in.

Also worth noting is that Church visited Newfoundland and Labrador to study icebergs before he produced the painting.

Polar Bears

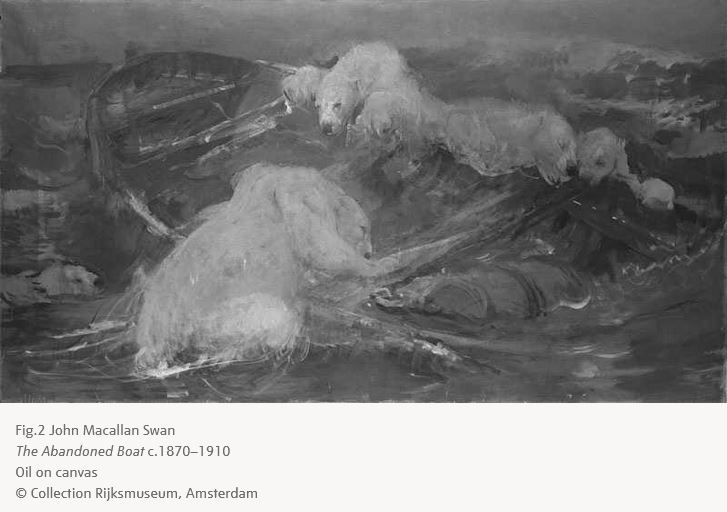

Then, as now, polar bears featured often in art in the nineteenth century. However, then the images were of the threat of the polar bears to man. Now, polar bears feature most commonly when the story is about the threat of man to bears.

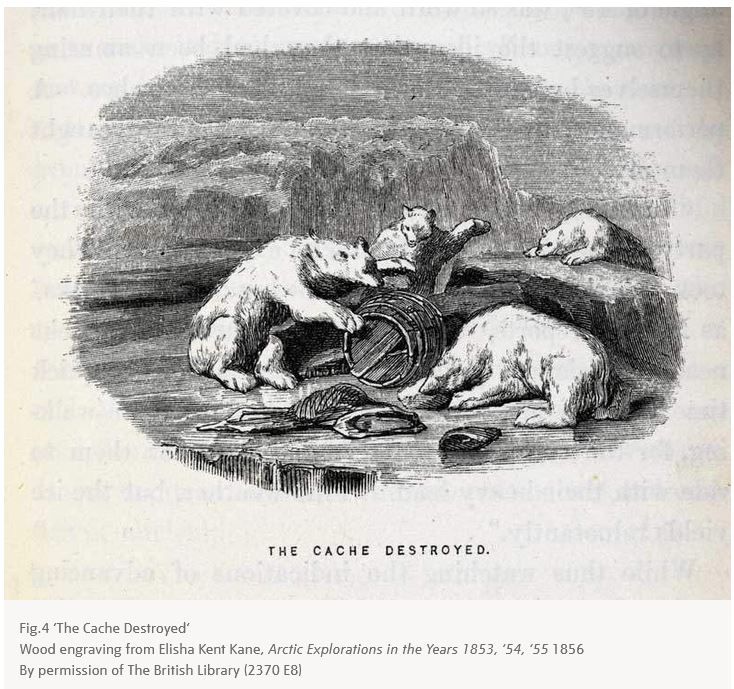

Artists responded to the public’s fascination with the danger and mystery of the Arctic and Arctic expeditions, often featuring polar bears to emphasise this. In addition, several wood engravings appeared in books published by the various leaders of expeditions, portraying the dangers they encountered.

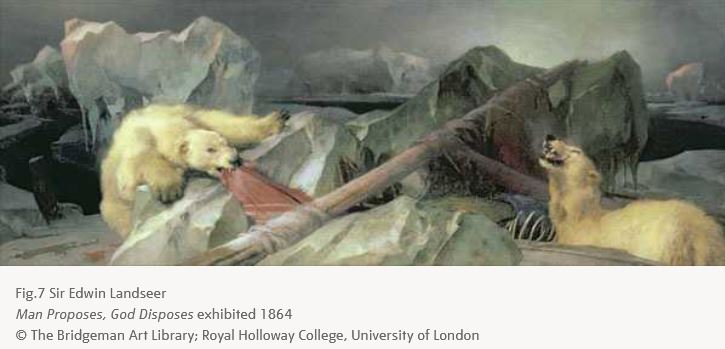

In Sir Edwin Landseer’s “Man Proposes, God Disposes” 1864 it is thought that the reference to God is more ironic than spiritual.

However, there is a violent edge to the scene, such that some think that the polar bears, in their devouring of remains, might also represent the notion of cannibalism. Apparently the painting received a cold reception by Lady Franklin and the Admiralty (understandably). However, it was one of the most popular paintings of the year, although later to be re-evaluated and described as gruesome.

Interestingly, at around the time of these painting being exhibited, Charles Darwin had published his “Origin of the Species” (1859) in which he proposes that evolution is at work in the survival of species through the struggle for existence. Darwin’s ideas and the depictions of a dangerous and brutal Arctic environment began to challenge the accepted notion of God being inherent in nature. It would have made for some lively art discussions, I bet!?

Greenlandic art

Aron from Kangeq (1822 – 1869)

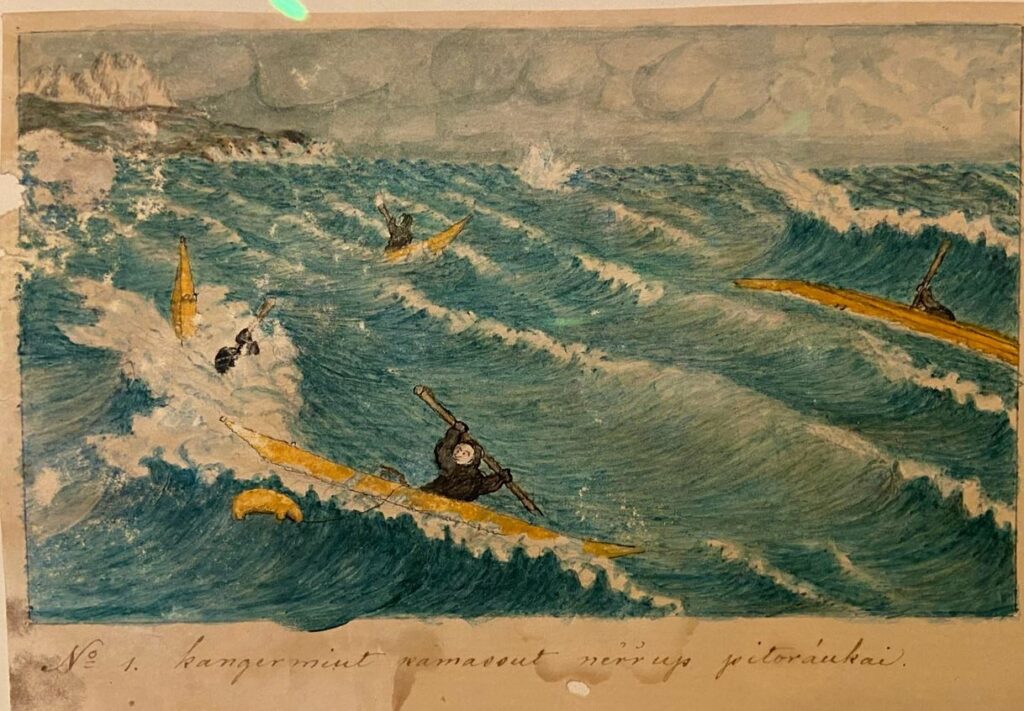

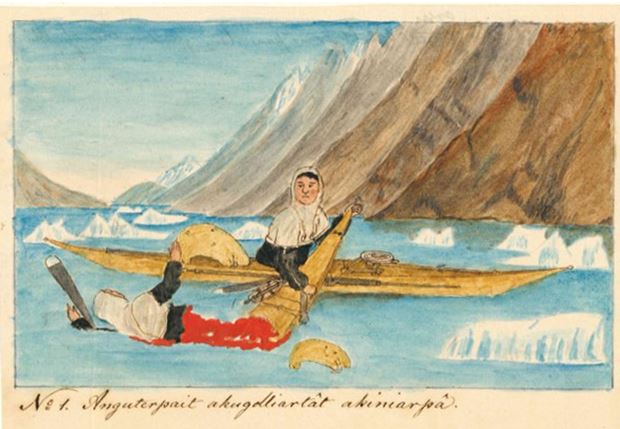

Aron from Kangeq was described in the church record of his death as a hunter and artist. His work includes fantastic drawings and watercolours of life in Greenland, particularly of their world of spirits, legends and witchcraft. We can see (and read) stories of violence and magic. Plus everyday life (hunting), as well as representations of the arrival of Hans Egede and the missionaries and their attempts to convert Greenlanders to Christianity. I discovered this video presentation of Aron’s work. Aron spent the last 10 years of his short life confined to bed, from where he did much of his drawing and painting, looking out the window to the bay of Kangeq. I am hoping that I will be able to see some of his work in the Nuuk Kunstmuseum.

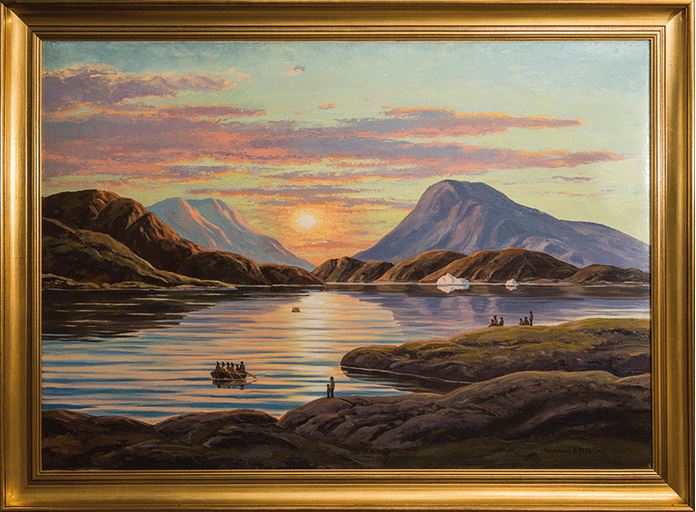

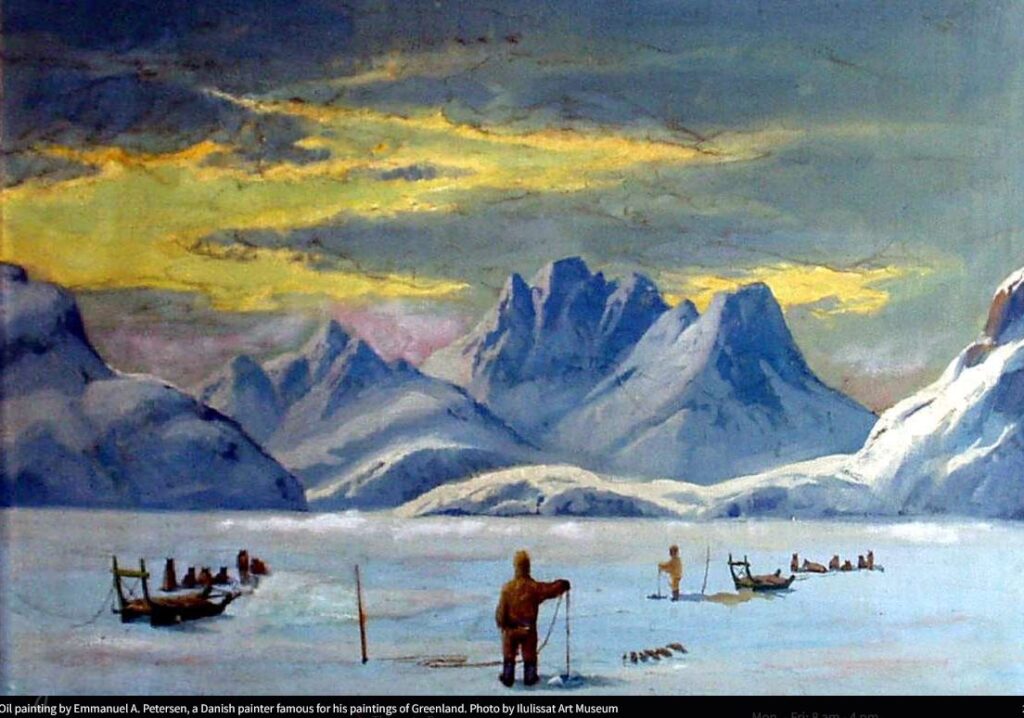

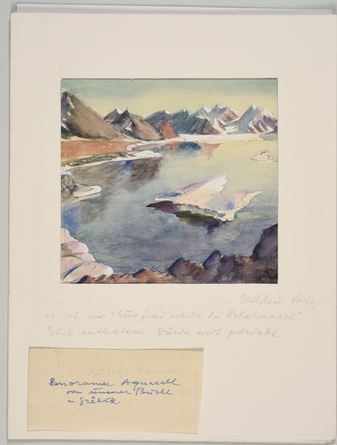

Emanuel A. Petersen (1894-1948)

Even though he was born in Denmark, Emanuel Petersen earned the name of “The Greenland Painter” due to his prolific work in painting Greenland landscapes after spending many years there from the 1920s to 1940s.

While Petersen’s paintings appear to display some of the ‘sublime’ characteristics of the earlier nineteenth century art described above, they do not contain the elements of danger or conflict. Rather Petersen wanted to portray the beauty and harmony of Greenland, in this way more consistent with the art of the Danish Golden Age.

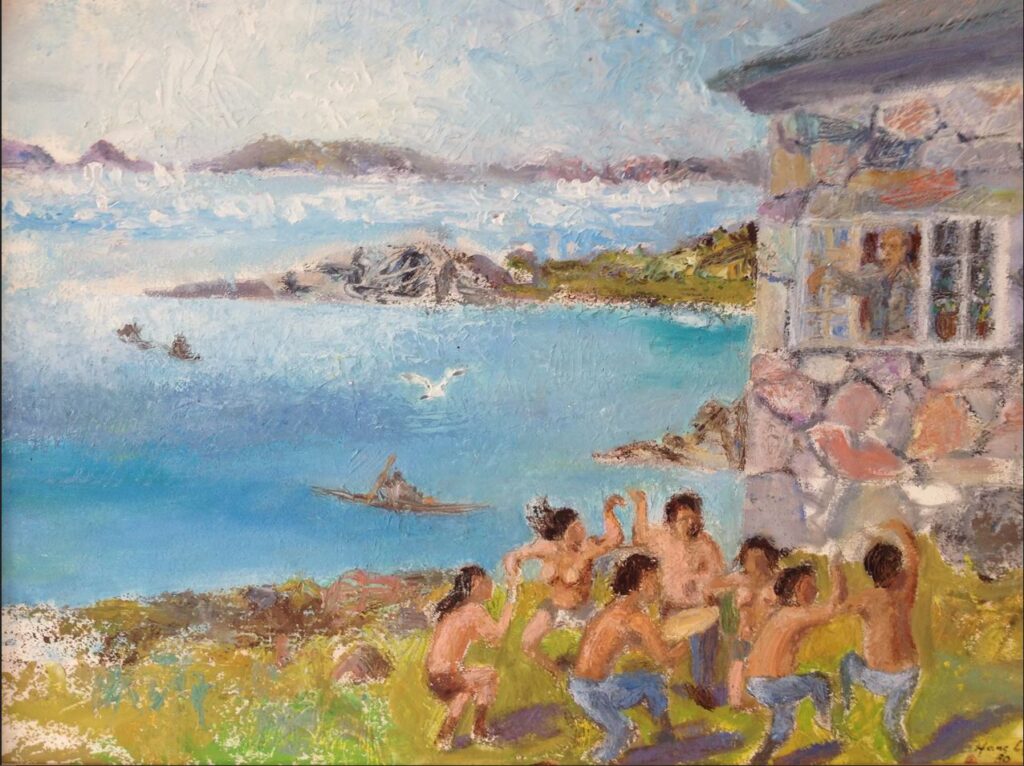

Hans Lynge (1906-1988)

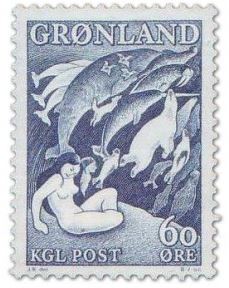

Hans Lynge was born in Nuuk and is considered to be an important and influential figure in the history of Greenland art. Themes in his art include myths, memories from childhood, women and mothers. The influence of Impressionism is visible in Lynge’s style.

Two of his paintings featured in Greenland Postage stamps

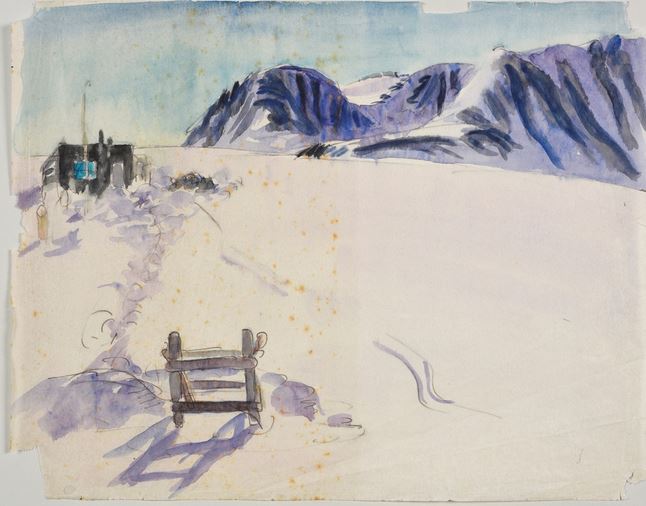

Christiane Ritter (1897 – 2000)

I know about Christiane Ritter because I read her book “A Woman in the Polar Night”, and was enamoured by it. Ritter spent a year in Svalbard, in a remote hut, with her husband and another hunter. The book is a memoir of her thoughts and experiences, as she coped with all the things which the long polar night brought.

I am mentioning Ritter here, though, because she was also an artist. In addition to the sketches which accompanied her book, Ritter painted a number of watercolours, both of the scenery, and of the hut where they lived.

I was very excited to discover that Ritter’s daughter donated a lot of her mother’s material to the Svalbard Museum in Longyearbyen. I’m hoping that they will be exhibited when we visit!

Meanwhile, I can’t help but share a quote from her book:

“How varied are the experiences one lives through in the Arctic. One can murder and devour, calculate and measure, one can go out of one’s mind from loneliness and terror, and one can certainly also go mad with enthusiasm for the all-too-overwhelming beauty. But it is also true that one will never experience in the Arctic anything that one has not oneself brought there.”

Jens Rosing (1925-2008)

Rosing was born in Ilulissat, , and lived intermittently in Greenland, Norway and Denmark. However, his art was firmly focussed on Greenland; on its traditions and stories.

Rosing created the artwork for many of the Greenland Stamps, often depicting the supernatural, myths and legends. In relation to the co-existence of Christianity and the relics of shamanism, Rosing is quoted to have said: “The star of paganism eventually lost its lustre, but it will not die as long as the northern lights continue to dance in the sky, as long as storms rage and surf crashes against bedrock, as long as the ice pack drifts in the wind and current under the torch of the sun”. (Source: Greenland Collector)

Greenland’s first commemorative stamp was designed by Rosing and featured a scene from a traditional story, ‘Mother of the Sea’.

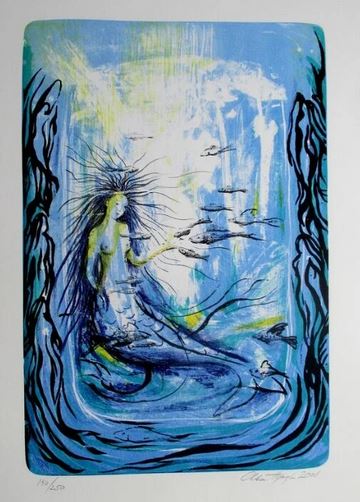

Aka Høegh (1947-)

Hoegh was born in Quillissat on Disko Island, and moved to Qaqortoq when she was young and has lived there ever since. Her works include painting, graphic art and sculpture, reflecting themes of traditional Greenlandic myths and legends. The legend of the Mother of the Sea is featured regularly in her art.

Hoegh is also known for her work in leading the “Stone and Man” outdoor sculpture project in Qaqortoq, where various artists contribute pieces to be included intermittently. I can’t wait to see this!

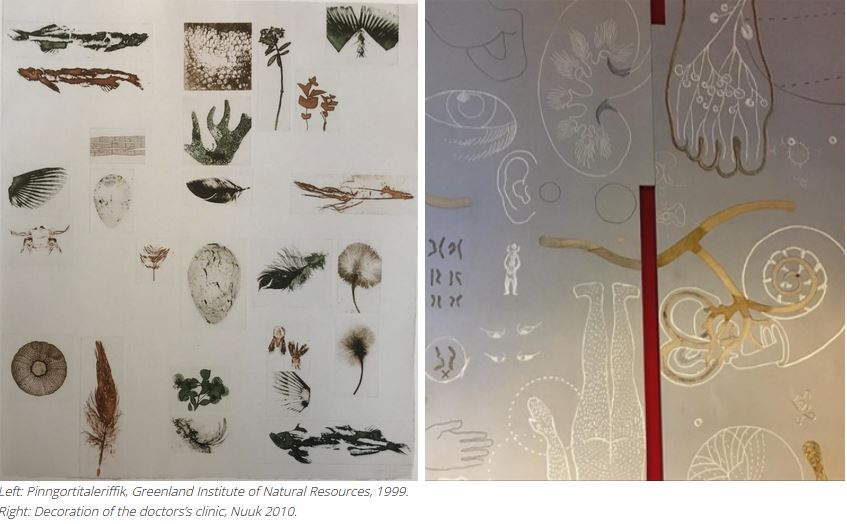

Anne-Birthe Hove (1951-2012)

Hove, born and raised in Greenland, is one of its acclaimed artists. She is know for her graphic art, using a wide range of materials and techniques. Having lived through periods of significant change in Greenland, Hove often incorporates social perspectives and human impact into her work, which are mostly commonly landscapes.

One series of work was of Sermitsiaq, a mountain overlooking Nuuk, were Hove photographed the mountain from the same position every day for a year. The resulting collection of images, produced using a graphic technique involving copper plates and coloured inks, is now in the Nuuk Art Museum.

Hove’s work was not confined to Greenland, as she found inspiration by travelling to other countries; South America, India and North America. Her expedition to the North American tundra generated a great deal of artwork, including many sketch books. Her interest in nature is particularly evident in the Tundra series.

A final note

Producing this post has been an interesting journey for me. At the outset, I thought that it would be a fairly simple exercise of gathering up some information about various artists – providing me with some advance knowledge, particularly about the Greenlandic art which I am hoping to see when I am there.

However, it has ended up being more than this for me, as I have discovered some context and connections. For example, the nineteenth century fascination with the danger and mystery of the Arctic, and the use of polar bears to elicit emotions from viewers. And then there is the passion of the Greenland artists to present their landscape and cultural heritage. And also the discovery that the Greenland postage authority has been so supportive of their artists as to reproduce their art (or indeed commission the artists) to provide the designs for their postage stamps on numerous occasions. And there is the undeniable fact that I am now curious about the Greenlandic myths and legends…

… will I have time to write about this before I go???

Sources

- “The Arctic Fantasies of Edwin Landseer and Briton Riviere: Polar Bears, Wilderness and Notions of the Sublime. By Diana Donald. Tate papers.

- “Aron of Kangeq” Sten Rehder. YouTube

- Nuuk Kunst Museum website.

- Visit Greenland website

- Greenland Today website.

- Ilisimatusarfik

- Greenland Collector

- The Philatelic Database

- MutualArt website