City Impressions: Stockholm

Stockholm was our first stop after leaving Sydney. And I don’t know what I imagined, but this quiet city was a little unexpected.

It was probably just the winder norm, but there were hardly any people in the streets. And the fog created a moody atmosphere, which persisted pretty much throughout the days. Rather than deterring us, it just added to the charm of our meandering around the old town. And to be quite honest, this was just the speed we were ready for, as we attempted to get over our jetlag as quickly as possible.

We had decided to take the boat out to the Vasa Museum. From the water the city sights, shrouded in fog, were even more atmospheric. Especially the amusement park which was closed for the winter!

It prepared us for the astounding sight of this seventeenth century warship.

In 1961, after 333 years at the bottom of Stockholm’s harbour, the Vasa was rediscovered. But it wasn’t until 1989, after a complicated salvage operation and preservation process, that she was ready for public viewing.

A more detailed history of the ship, and of the king who commissioned its construction, can be found here on the Vasa Museum website.

Meanwhile, below are some of the key points:

- The ship was commissioned by King Gustav Adolf of Sweden, who was expanding his fleet during a period of intensive warfare (Gustav was at war in 18 out of 21 years of his reign, as he built Sweden into a fearsome European power)

- Construction of the Vasa, which was to be the most powerful warship, commenced in 1626 when the keel was laid.

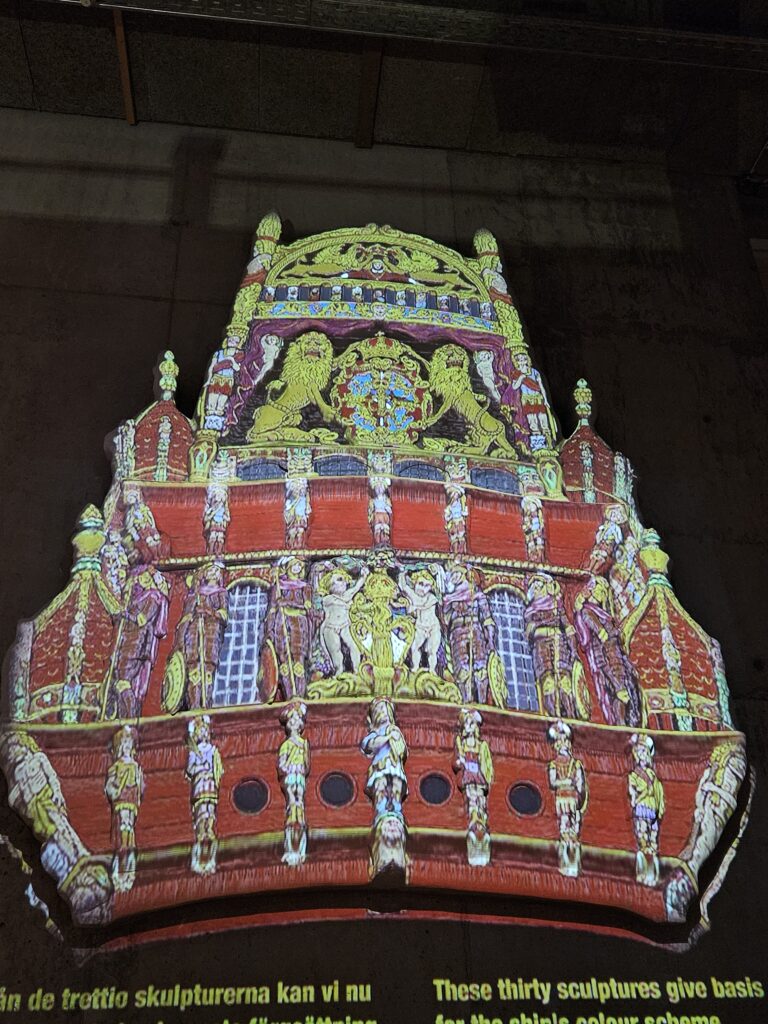

- In 1627 the Vasa was launched. It was 69 metres long and 50 metres tall, and weighed 1,200 tonnes (including its sails). It had 64 cannons, 120 tonnes of ballast. It was (is) decorated with hundreds of carvings and sculptures.

- Yet to embark on a maiden voyage, there were serious concerns about its seaworthiness. On one occasion the construction supervisor demonstrated to the Vice Admiral how the ship rolled when he had 30 men run from side to side across the deck.

- Regardless of these concerns, the ship set sail on 10 August 1628. It went no further than 1,300 metres, where it listed to port and sank in minutes, still within sight of the shipyard.

- In addition to the crew, there were guests on board, including women and children. All but 30 survived. However, the names of all of those who perished that day are still not known.

- There was an inquest into the incident, and the designer was blamed. Henrik Hybertsson was not punished – he had been dead for more than a year.

- Most of the ship’s cannons were retrieved within decades of the sinking. But repeated attempts to float the ship failed.

- In 1920 an application to blow up the ship to salvage its timber for furniture making was denied.

- The Vasa was lost in the mud at the bottom of the harbour until 1956 when it was rediscovered.

- Then, after many twists and turns in the operation, the ship finally surfaced on 20 April 1961.

The sculptures which adorn the ship were painted in bright colours, designed to demonstrate both the power and wealth of Sweden. As I gazed upon these intricate and intriguing works of art (even in their current unpainted state) I was astounded at the extraordinary amount of time and resources which went into the build of the Vasa.

I remember talking to one of the volunteers at the museum who explained that the ship was simultaneously a source of embarrassment and pride.

Embarrassment, because a King of Sweden should make such a monumental blunder in supporting the enterprise. Pride, because the Vasa has become a world-wide source of information and inspiration, for the way it was salvaged and restored, and for the priceless insight into the era.

![IMG-20250127-WA0002[1]](https://roughseas.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/IMG-20250127-WA00021.jpg)