“Arctic Dreams”

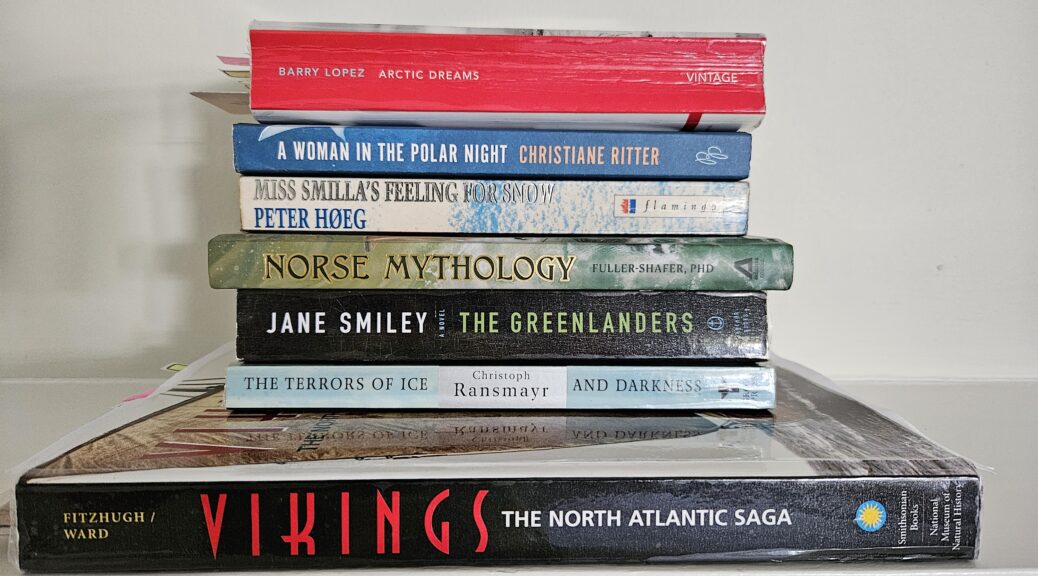

As you can see, I’ve gathered some reading material. And I suspect the pile will grow over the next few months. I just hope that I can read it all before I leave!

Meanwhile, the first book I’ve read was a Christmas gift. A classic called “Arctic Dreams” by Barry Lopez. Lopez is known for his passionate writings about remote areas, and about the relationship between us and the land we inhabit. And more importantly, about the impact we have had, and are still having, on that land.

It is hard to describe this book and do it justice, because it is many things at the same time.

In it Lopez describes in language which is thought provoking and sometimes philosophical, the experiences he has while travelling and working in various Arctic regions, often accompanying scientists or local indigenous groups as they work and live.

“At the heart of this narrative, then, are three themes: the influence of the arctic landscape on the human imagination. How a desire to put a landscape to use shapes our evaluation of it. And, confronted by an unknown landscape, what happens to our sense of wealth.”

Lopez describes the natural environment and its animal inhabitants. He describes how different cultures and different groups have interacted with the land over time. He ponders on the power which we have to influence and shape the Arctic of the future, and he considers the mistakes which have been made in the past.

“ A Yup’ik hunter on Saint Lawrence Island once told me that what traditional Eskimos fear most about us is the extent of our power to alter the land, the scale of that power, and the fact that we can easily effect some of these changes electronically, from a distant city. Eskimos, who sometimes see themselves as still not quite separate from the animal world, regard us as a kind of people whose separation may have become too complete. They call us, with a mixture of incredulity and apprehension, ‘the people who change nature’.”

There are a couple of chapters in the book where Lopez describes both the early migrations of peoples into the area, and then the later exploration and commercial expeditions. A common theme is that the later visitors did not always pay attention to the learned knowledge of the inhabitants.

“Western society on its own has long held in low esteem human cultures that matured outside the Temperate Zone, a confusion, in large part, about what the landscapes these people lived in demanded of them.”

And even more damning…

“The spheres of separate knowledge of the mapmaker, the able-bodied seaman, the whaling captain, the Eskimo and the British naval officer were kept segregated through contempt and condescension, and by social policies that divided people on the basis of education, race, social class, and nationality. Although this pattern of intolerance has long been a pattern of human life, it is especially in the area of geographic knowledge that these rifts are lamentable.”

Moreover, Lopez points out that the descriptions of exploration in the arctic are presented as battles where the land is the adversary, to be conquered and tamed. And that explorers who did not ‘succeed’ in their quest somehow failed.

However, Lopez would rather this war with nature be viewed as a “human longing to achieve something significant, to be free of some of the grim weight of life”.

And then Lopez mentions Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the companion of Robert Scott, and quotes Cherry-Garrard when he said that “exploration was the physical expression of an intellectual passion”. Lopez believes that this summation still holds true, even for the men who underwrote expeditions for commercial gain. He believes that “intellectual passion” can be interpreted to be whatever someone perceived was to be found at the end of the quest.

Mentioning Cherry-Garrad as he did, at this moment, Lopez has made me think a little further about the differences in the motivation for exploration at the Poles. You see, I read Cherry-Garrard’s book, where Lopez took this quote, when I was preparing for my Antarctic trip. (See this post and this one also) It appears to me that the motivation behind Westerners exploring the Arctic was more openly about finding new areas to exact financial gain; either in opening up a trade route, or in hunting for skins and ivory (i.e. walrus tusks).

Throughout the book Lopez circles back to the dilemma mankind faces in deciding how to live well.

“What every culture must eventually decide, actively debate and decide, is what of all that surrounds it, tangible and intangible, it will dismantle and turn into material wealth. And what of its cultural wealth, from the tradition of finding peace in the vision of an undisturbed hillside to a knowledge of how to finance a corporate merger, it will fight to preserve.”

The message which I heard throughout the book was mankind’s occupation of earth has often been one of domination and exploitation. But we now need to take time to learn from and listen to the land.

Interestingly, it was in the preface to the book where I found this quote, a sign of hope which we would do well to act upon before it’s too late.

“We have been telling ourselves the story of what we represent in the land for 40,000 years. At the heart of this story, I think, is a simple, abiding belief; it is possible to live wisely on the land, and to live well. And in behaving respectfully toward all that the land contains, it is possible to imagine a stifling ignorance falling away from us.”

And a closing quote…

“Whatever evaluation we finally make of a stretch of land, however, no matter how profound or accurate, we will find it inadequate. The land retains an identity of its own, still deeper and more subtle than we can know. Our obligation toward it then becomes simple: to approach with an uncalculating mind, with an attitude of regard. To try to sense the range and variety of its expression – its weather and colours and animals. To intend from the beginning to preserve some of the mystery within it as a kind of wisdom to be experienced, not questioned.

And to be alert for its openings, for that moment when something sacred reveals itself within the mundane, and you know the land knows you are there.”